標籤: 老師

秋之天問(為我的吳忠吉老師)

經過了整個台北城瘋狂赭紅到令人不安的台灣巒樹,我趕到台大醫院加護病房已經是下午兩點一刻了,老師,第一眼看見您的時候那淚水終究是被我忍住了。穿上了隔離衣,戴上口罩,那深冷白冰的不鏽鋼門緩緩打開,4B2,一個憔悴的婦人坐在病榻旁,是師母。引我坐在您的插滿管子的身旁。說了一些您自七月在師大上課不小心跌倒送醫院以來的種種,本來要出院了,卻因為醫院的誤診而導致病情加重,終至昏迷腦死。「為什麼?」「這是什麼醫院什麼世界?」「是誰奪走我的恩師?」我的心裡憤怒地問。師母以一種非常平和的語氣說著七月以來老師在醫院裡的起伏。我假裝靜靜地聽著。看著人工呼吸機器供應著老師的一分鐘8次的呼吸的次數。看著老師微開無法轉動的眼睛。前塵往事歷歷在前。「老師還是聽得到你說話,我出去,你是老師的得意門生,你跟老師好好說說話,但不要哭」,師母說著就走出病房。我坐下來。想握著老師的手,但觸不著。我只好搭著老師的肩,跟老師說話。

老師,學生來晚了。整整遲了三個月。非常的自責。若不是昨天到台大去講課,我還不知道。老師。您是我的恩師。照顧我最多。啟蒙我最多。教誨我最多。在我的那青春瘋狂的台大青年時代。特別是1985年的那年5月,我們佔領了傅鐘,並且發動了有史以來最大的學潮。國民黨的軍警把台大外圍團團圍住,便衣刑警到處都是。老師,您記得嗎?在那時候,有一天你忽然把我找到傅鐘旁的行政大樓您當註冊組長時的辦公室去,拿出一份名單,說「警備總部已經知會孫震校長,學生運動已經危及社會國家安全,這23人名單中有計生你,你要小心。但老師會全力保護你們的,我會跟校長說,學生們爭取言論自由,出版自由是純潔的,沒有任何其他目的的。」老師,我們沒有一個人在那次運動中被逮捕,不用說就是您的說項奏效了。若沒有您,老師,我想我的一生是完全地不同,可能在綠島步上政治犯的後塵,也可能曝屍荒野。老師,謝謝您!你給我的是一份對於土地不悔的愛, 一種為理想奮不顧身去追尋知識的無上勇氣與毅力,一個從擦鞋童變成台大經濟系教授的無產階級找到自己的典範。老師,我把昨天寫在部落格的心情現在再說一遍給您聽:

「就是昨日下午至台大普通教室504講授「文學中的台大」課程,於中間休息時一經濟系學生問問題,閒聊之際,驚聞我的恩師吳忠吉教授重病住院,第二節課上來精神分離,力掩心中擔憂不定,午夜輾轉反側猶不得眠。我那時是唸經濟系的大三時代終於敢和導師老師深談就是在當時只有兩層樓的普通教室。我在一樓的教室外等吳老師下課,看他在黑板寫著高深莫測的數學公式會心一笑,知道那只是戒嚴時期的偽裝。老師出來後就跟我一起步行走向新生南路,「計生,你那厚重的包包裡裝的是什麼?」「一些馬克思理論,和社會主義的東西」,老師咧嘴用台語笑著拍拍我肩膀說「金好,金好」,我跟著笑,感覺在一個人人想去美國留學或進銀行上班的沒人理解我為什麼搞學生運動抵抗戒嚴體制的時代有個暗夜明燈的溫暖,一路跟老師一起到懷恩堂那頭的咖啡廳繼續討論。吳老師最為驚人的能力,是能夠用主流經濟學的P&Q圖式直接畫出資本家是如何剝削勞工而非法佔有剩餘價值(即超額利潤),我記得當年在那昏黃咖啡廳下聽得目瞪口呆!原來主流經濟學與馬克思理論並非我想像中的遙遠,這啟迪了後來我在《馬克思學–經濟先行的社會典範論》書中的打通馬克思與凱因斯經濟理論的艱鉅工作。憶起吾師在我的戒嚴時期的大學時代,於政治經濟學的教誨、口傳心授堅決理想的意志和呵護有加的生活關懷,使我這到處尋找回家的感覺的漂泊心靈不禁潸然淚下。噫!悾傯世事,國事飄搖,而師恩此生難報,繼起者可不孜矻於大愛傳播與追求永恆之事業者乎。」老師,您一定記得普通教室前的我們的對話吧

老師,我很想念您,很愛您。今年中秋寄柚子到您家沒有接到您的電話當時就覺得有點奇怪,後來瞎忙就沒問您,沒想到就出事了。老師,學生來晚了。整整遲了三個月。非常的自責。若是三個月前,我想以我的氣功能耐一定可以幫老師復原。現在。老師,我只能對您看來像是自言自語地說給您聽。我哽咽了幾次。無法言語。我繼續說,心中充滿悲傷,但我不流淚。師母說。不流淚。

師母進來了。帶著一種秋盡冬將至的蒼涼,宛若巒樹的燦爛黃花晦暗成赭紅的憂鬱,口罩上方疲憊的眼神看著我,示意要我洗了手到外面繼續說。老師。您不用聽也知道。以您的過人智慧與毅力知道時之將至,可以放手去天國。老師,是作學生的不捨。您才63歲。學生要跟您學習的東西還很多。您跟我說「不要當第一個站起來的人,要當最後一個倒下的人」為什麼現在您要棄學生而去,讓我孤單一人面對這險惡世界?老師,我問秋天的蒼天,它只給我濛濛細雨的回答。不是一個回答,而是敷衍。所以。老師,我要您醒過來,您一定要醒過來,我要為您求遍天下神祇,或者無神論的堅強意志也可以。你前半生的台北街頭吃苦的意志,在我大學時代就已經完全感染了我,現在,老師,學生要求您感染您自己,從死神掌中脫離,回到這多麼需要您經濟學智慧的台灣!回到只學到您一身功夫萬分之一的學生旁,再親自接受您的教誨。老師,剛才我還對您說了這些話,您聽見了嗎?

秋之台北城,一樣忙碌,我從台大醫院趕回外雙谿研究室準備開會前寫了這些。學生打電話來催。我說等等。這些冗長假民主的鬼會都必須等等。我必須寫完這些。我必須對秋天的宇宙發問,而灰白相間走得極快的浮雲,預示著風雨或許將至,我的胸臆焚燒著即將喪親之痛的篝火,把眼前的校園裡的台灣巒樹燒的更為火紅,更為悲涼,更為思念我的老師吳忠吉。而背手轉身出了308研究室右轉扶著陳舊鐵欄杆抬頭所見,濛濛細雨裡,一道意料之中的彩虹意料之外在我的淚痕中出現,從故宮的方向彎向市中心的台大醫院,老師,加護病房4B2,您在那裡沈著呼吸著,也看見了這聯繫我們師生情誼的七種色彩交織而成的無窮無盡變化的彩虹嗎?您必然也看到了吧,已經五點多了,天逐漸黯淡下來了,老師,您好好睡,明早醒來,學生再說些以前我們有趣的掌故給您聽。老師,您好好睡,彩虹裡安眠,祝您有個美麗燦爛的夢,我在黎明來臨時等您,一起公館溫羅汀散個步,說說天下大事,人生哲理,與這個屬於秋天應該有的期盼過了冬天,春天就會不遠,彩虹會消散,老師,我對您的愛永不止息

(2008.10.16)

老師,在我們渡過的那個只知道解除魔咒卻不知留下記錄的時代,學生突然發覺經過了二十多年的相處,無數次見面、聚餐與討論學問,我竟然連一張和老師您的合照都沒有,我只能放上昨天下午瞥見的彩虹成為一座橋,聯繫這頭與那頭。我昨天看著您無法回首動彈的臉,假裝沒事地走了,和師母道別,和您的大女兒還在台大經濟所唸博士班的女兒道別,回來山林懷抱中的外雙谿,我寫下了「秋之天問」,我假裝沒事開會,讓書僮離開讓生活自己,我努力讓自己安靜。我確實安靜了。然後另一個白天來臨,我打開電腦。老師,我發覺這世上還是有很多人關心您。您以前的學生。豆腐魚。以及其他人。寫e-mail信來。說「我們都很關心吳忠吉老師」。還說要去4B2看您。給您力量。老師。我現在坐在308研究室。聽著學生捎來的陳昇「把悲傷留給自己」。我已經很久不曾如此濫情到任意淚流滿面。在獨自一人的空間中,我想是合理的,被允許的。老師,我看著窗外的一樣的老榕樹。與後面的女生宿舍。一些不會再回來的人影。我往後看。更高的雞南山後。不會再回來的爬坡撐傘旅行。我再往後看。不會再回來的台北盆地的南方。在法學院。在溫羅汀。您以威嚴清晰的論證,單刀直入地說明資本主義經濟的真相。站在勞工這一方的發言。記得當時要出國留學時,您還要我去讀倫敦政經學院,說那裡是馬克思的第二故鄉,勞工研究非常的好。回來可以貢獻所長。為台灣。後來我去了芝加哥。回來應徵教職。有幾個可能。當我懸而未決時,我心裡想到的第一個問的人就是老師您。後來又有機會轉到別的學校去。我也是問您的意見。老師。事實證明。您給我的意見都是對的。更早之前,甚至,我所認識的女孩,也要讓您與師母看過才是安心的,雖然我這個人漂泊無定性十足浪子如您所說的有你年輕時的影子。老師,您記得那時師母為了你健康家裡禁煙那次您假借送我下樓從你家中偷溜下來一起抽煙時您笑著跟我說的話嗎?「雖然天性流浪,但每次的愛都要專注泊港,直到緣聚緣散,一如清風吹白雲」,4B2中沈著呼吸的您,老師您記得嗎?

但老師,我們這麼親近,從那解除戒嚴魔咒的時代迄今,為何我們竟然沒有一張合照呢?是不是因為我一直覺得您作為我生命中的明燈,會永遠在那裡呢?還是您刻意留白讓我必須一輩子用文字記住您的影像呢?我在研究室俯首,書寫,抬頭,你的影像無處不在。略呈倒三角形的頭顱,顯示巨大腦容量蘊含龐大的思維能力,兩顆炯炯有神的眼睛威嚴沈著地看著我,令不認識您的任何人不寒而慄。但是,當您一開口,或者聽到您的綿密推論、笑聲與台語時,我整個向來戒備不信任人精神分裂的心就如融化的冰雪,與您愉悅交融,如沐春風。老師,我在東吳上課時。少數親近的學生曾經用這樣的眼神與距離形容我。那冰雪融化的感覺也是一樣的。老師。我想我正繼承起您的傳道授業解惑的衣缽吧。老師,書寫了這一嚮午。我的剛才的眼淚也隨著太陽雨的狐狸嫁完女兒的停歇光影輕灑在老榕樹紛吐的褐色氣根上閃爍風中飄逸風乾了。老師,我和眾多您教過的台大的,師大的或者其他學校親炙或私淑的學生們一起祈禱著奇蹟出現。您一定要醒過來。跟我好好照張相。老師,我會說服師母的,可以的,一起抽跟煙,照張相。不然我也會拿起狐狸給我的那把小刀披荊斬棘,到那千萬種顏色的廣漠山谷盡頭所見的碩大無比的彩虹前,去找尋老師您的靈魂所要去的地方,那吳忠吉經濟學所構成獨一無二的美學,不分階級的真善美的究竟之地,老師,那影像,那域土,我以一生的心力去追尋

(2008.10.17)

Movie Critics: On Cape No. 7(Interview)

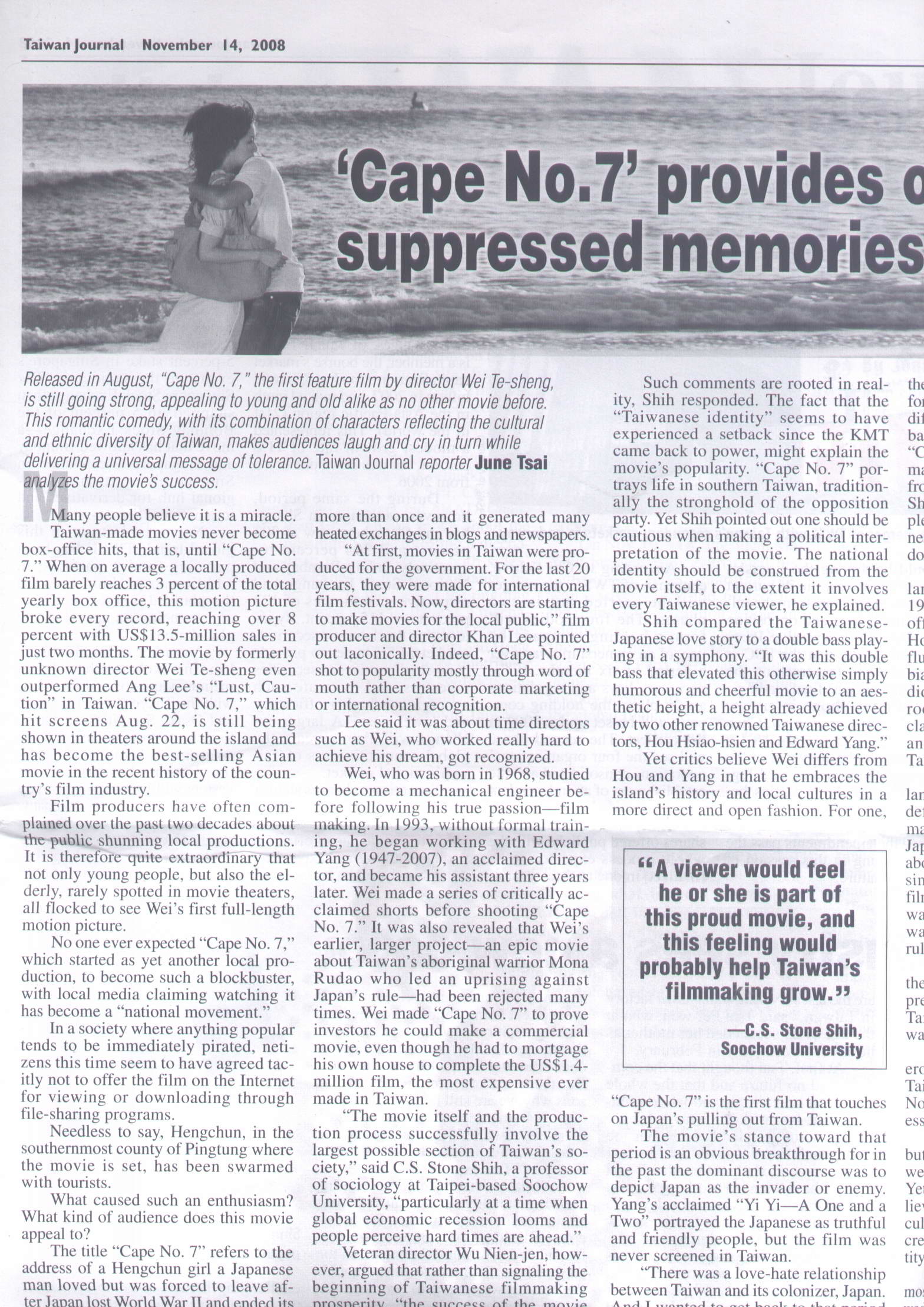

石計生教授(C.S. Sone Shih)接受英文週刊Taiwan Journal專訪評論電影《海角七號》Vol. XXV No. 45 November 14, 2008

Taiwan Journal Website http://taiwanjournal.nat.gov.tw/ct.asp?CtNode=122&xItem=46100

Cape No.7′ provides outlet for suppressed memories, feelings

Released in August, “Cape No. 7,” the first feature film by director Wei Te-sheng, is still going strong, appealing to young and old alike as no other movie before. This romantic comedy, with its combination of characters reflecting the cultural and ethnic diversity of Taiwan, makes audiences laugh and cry in turn while delivering a universal message of tolerance. Taiwan Journal reporter June Tsai analyzes the movie’s success.

Many people believe it is a miracle.

Taiwan-made movies never become box-office hits, that is, until “Cape No. 7.” When on average a locally produced film barely reaches 3 percent of the total yearly box office, this motion picture broke every record, reaching over 8 percent with US$13.5-million sales in just two months. The movie by formerly unknown director Wei Te-sheng even outperformed Ang Lee’s “Lust, Caution” in Taiwan. “Cape No. 7,” which hit screens Aug. 22, is still being shown in theaters around the island and has become the best-selling Asian movie in the recent history of the country’s film industry.

Film producers have often complained over the past two decades about the public shunning local productions. It is therefore quite extraordinary that not only young people, but also the elderly, rarely spotted in movie theaters, all flocked to see Wei’s first full-length motion picture.

No one ever expected “Cape No. 7,” which started as yet another local production, to become such a blockbuster, with local media claiming watching it has become a “national movement.”

In a society where anything popular tends to be immediately pirated, netizens this time seem to have agreed tacitly not to offer the film on the Internet for viewing or downloading through file-sharing programs.

Needless to say, Hengchun, in the southernmost county of Pingtung where the movie is set, has been swarmed with tourists.

What caused such an enthusiasm? What kind of audience does this movie appeal to?

The title “Cape No. 7” refers to the address of a Hengchun girl a Japanese man loved but was forced to leave after Japan lost World War II and ended its colonial rule of Taiwan (1895-1945). On his way back to Japan, the man pours his love and regrets into seven letters that he never sends. Sixty years later, the man’s daughter finds the missives after her father’s death and decides to forward them to their rightful owner.

Meanwhile in Hengchun, Aga, an aspiring rock singer, has just come back to his hometown after failing to find success in Taipei. His stepfather–a town representative–is determined to set up a local band and have it play as the opening act of a young Japanese star’s concert. The band has three days to get ready. The movie follows the band’s preparations during this short period.

Viewers laughed throughout the movie before leaving the theaters with tears in their eyes. Many people saw it more than once and it generated many heated exchanges in blogs and newspapers.

“At first, movies in Taiwan were produced for the government. For the last 20 years, they were made for international film festivals. Now, directors are starting to make movies for the local public,” film producer and director Khan Lee pointed out laconically. Indeed, “Cape No. 7” shot to popularity mostly through word of mouth rather than corporate marketing or international recognition.

Lee said it was about time directors such as Wei, who worked really hard to achieve his dream, got recognized.

Wei, who was born in 1968, studied to become a mechanical engineer before following his true passion–film making. In 1993, without formal training, he began working with Edward Yang (1947-2007), an acclaimed director, and became his assistant three years later. Wei made a series of critically acclaimed shorts before shooting “Cape No. 7.” It was also revealed that Wei’s earlier, larger project–an epic movie about Taiwan’s aboriginal warrior Mona Rudao who led an uprising against Japan’s rule–had been rejected many times. Wei made “Cape No. 7” to prove investors he

“The movie itself and the production process successfully involve the largest possible section of Taiwan’s society,” said C.S. Stone Shih, a professor of sociology at Taipei-based Soochow University, “particularly at a time when global economic recession looms and people perceive hard times are ahead.”

Veteran director Wu Nien-jen, however, argued that rather than signaling the beginning of Taiwanese filmmaking prosperity, “the success of the movie has more to do with suppressed popular feelings having found an outlet at last.” The fresh film combines distinctive elements of the local Taiwanese culture that appeal to people’s feelings, in particular during politically perturbed times, he observed.

His views echo the editorials of some major Chinese-language newspapers. The Apple Daily described the film as “hitting right on the psychological reality of the rising Taiwanese consciousness.” The China Times praised it as a “love letter to Taiwan,” highlighting “the island’s collective memory.” The New Taiwan Weekly magazine said the film carves out an aesthetic appropriate to the country’s popular culture, systematically suppressed since the end of World War II under the Kuomintang rule.

Such comments are rooted in reality, Shih responded.The fact that the “Taiwanese identity” seems to have experienced a setback since the KMT came back to power, might explain the movie’s popularity. “Cape No. 7” portrays life in southern Taiwan, traditionally the stronghold of the opposition party. Yet Shih pointed out one should be cautious when making a political interpretation of the movie. The national identity should be construed from the movie itself, to the extent it involves every Taiwanese viewer, he explained.

Shih compared the Taiwanese-Japanese love story to a double bass playing in a symphony. “It was this double bass that elevated this otherwise simply humorous and cheerful movie to an aesthetic height, a height already achieved by two other renowned Taiwanese directors, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang.”

Yet critics believe Wei differs from Hou and Yang in that he embraces the island’s history and local cultures in a more direct and open fashion. For one, “Cape No. 7” is the first film that touches on Japan’s pulling out from Taiwan.

The movie’s stance toward that period is an obvious breakthrough for in the past the dominant discourse was to depict Japan as the invader or enemy. Yang’s acclaimed “Yi Yi–A One and a Two” portrayed the Japanese as truthful and friendly people, but the film was never screened in Taiwan.

“There was a love-hate relationship between Taiwan and its colonizer, Japan. And I wanted to get back to that period of mixed feelings,” Wei said in a September interview. The movie brought back many unspoken memories moving some elderly viewers to tears.

“Cape No. 7” appeals to most viewers because it epitomizes the kaleidoscopic aspects of the country. The movie addresses its many contrasts without ever taking sides.

Choosing Hengchun as the backdrop is in itself symbolic as it contrasts with metropolitan Taipei, while the town shows signs of contradictions in its progress toward modernity. It has retained its old city walls but has built five-star hotels; it hosts the “Spring Scream” rock festival but is also home to Hengchun folk music.

Moreover, there is an aboriginal policeman and a Hakka salesperson to underline Taiwan’s ethnic diversity, while the 80-year-old postman and the nonconformist young pianist serve to encompass different age groups. Also the amateur band is training in Western-style pop. “Cape No. 7” may lack waishengren –mainlanders who immigrated to Taiwan from mainland China after the war–yet, Shih reminded, most of the young people in the movie speak Mandarin Chinese, and “it is this ‘absent subject’ that dominates the screen.”

When the KMT moved to the island after the Chinese civil war (1946-1950), it made Mandarin Chinese its official language, effectively banning Holo-Taiwanese. Such proscription influenced the media and created certain bias toward the language. Some viewers did criticize the prevalent use of grassroots slang in the film, while others claimed it is overshadowed by Japanese and American subcultures and lacks Taiwanese components.

However, “the use of these various language elements is deliberate,” Shih defended. “It is natural for the old postman to be able to speak Japanese to the Japanese program coordinator, for the aboriginal policeman and the failed rock singer to fight in Chinese.” Even the film’s motif, Schubert’s “Haidenroslein,” was carefully chosen because the lied was popular during Japanese colonial rule of the island.

“The director has interwoven all these ethnic and cultural elements very precisely to reflect the life of ordinary Taiwanese, and he depicted them in a warm and tolerant way,” he argued.

“It is the assimilation of these heterogeneous cultures that make up the Taiwanese identity,” Shih said, “‘Cape No. 7’ grasps that. It cuts right into the essence of the Taiwanese culture.”

“Taiwan experienced several rulers, but the people never had their say. We were educated in the rulers’ languages. Yet when it comes to our identity, I believe we assimilated aspects of various cultures into our own indigenous one to create a truly original Taiwanese identity,” the professor continued

Because the daily experiences of most people in Taiwan–the raucous wedding banquet, the macho gangster-like local representative, the depopulation of small towns and its related social problems, for example–are all so accurately represented, and because what was once considered as vulgar and cheap is depicted in a benevolent manner, “a viewer would feel he or she is part of this proud movie, and this feeling would probably help Taiwan’s filmmaking grow,” Shih said.

Director Wei attributed the popularity of “Cape No. 7” to the energy inherent to the people of Taiwan. “What Taiwan wants is a consensus [on its identity]. Once the consensus is built, an unimaginable energy would result from it,” he said. Judging from its performance, the movie might as well be the current common denominator for people of every political spectrum on the island.

這時黯淡的夜–悼我的老師吳忠吉(1946-2008)

老師,剛剛我去監考大一社會學的期中考,巡視一回,回來研究室,天半明半暗之間,我端坐焚了檀香的桌前修改即將要到北京大學發表的學術文章,心裡還是想著怎樣催一催唐山書店,把馬克思學的要獻給您的書改好正式出版,帶到台大醫院唸給您聽。一通社會系秘書轉來的辦公室電話完全讓我的希望破滅了。您的兒子打來的。用沈靜的口吻說您已經於2008年10月30日過世。我噙著淚水不願意在後輩前失態。但是。老師。當我聽到師母的聲音我就崩潰了。潰堤的淚水泣不成聲。師母說您從過世的第一天就在找我。大家都想聯絡我這個幾乎不用手機的人。誦經的師父也提起我。到了做頭七的今天。終於找到了我這個再次喪父之人。才知道為何這幾天一直轉轉反側無法入眠。

師母電話裡說,我就像您的孩子。情同父子。您一直都惦記著我的日常生活和學術生命。老師。自從在戒嚴時期的台大做您的學生以來,我從來就把您當作我的親人,我一生中不可或缺的典範。1994年我父親過世,沒告訴您。我記得後來我們聯絡時,您非常生氣地說:「這麼大的事情,為何沒告訴老師,這樣我一生都不會原諒你!」老師,我那時到底基於怎樣的心理我也不知道。或許是叛逆。一種心理的故意的距離。對於最親近最愛的人總是隱晦躲藏不提或者離的遠遠地。老師,我本來以為我也當教授之後就成熟了,不會再有這樣的心理了。但是。這次又發生了。我總希望以最為完美的姿態面對所愛。要「最完美」。所以就想把您所教導我的經濟學的部分所出版的書,要以在扉頁上書獻給您的姿態帶在身邊,再回到台大加護病房4B2唸給您聽。但是。老師。我又太遲了。我很懊悔。我再次的喪父,卻不能即刻在您身邊課頌地藏菩薩本願經。在今天晚上還有課的必須徹底精神分裂地面對學生。心中的痛苦無法言語。老師,這時黯淡的夜,完全說明了「社會人」的無奈。

老師,您是能瞭解的。但我無法接受您以63歲之齡離我而去。上天是不公平的。竟如此冷血奪走師母的先生,您孩子的父親與我的生命的重要構成一角。爾今爾後。老師,我的生命是殘缺的了。有一個地方是無法被填滿的了。是永遠在黑暗裡找尋出路的徬徨。是一種我對於您所造就我的一切的無法報答的創痛。我何其幸運,有您這樣的 父親,在那戒嚴時代導引,鍛鍊出我和您一樣從三重埔路邊賣鞋混跡現實苦讀自修成為教授的鋼鐵般的生命意志。我何其幸運,有您這樣的 父親,讓我總是學您面對難題,心懷溫暖與科學的精神勇於面對。我何其幸運,有您這樣的 父親,讓我雙腳緊緊和台灣這塊土地關連,永遠看著我們的山我們的河,並且不忘從兩岸,從亞洲,從全球,從最大的格局設想解決台灣的生存難題,找尋出路。「經世濟民,乃若其情。」老師。您記得您曾稱讚我的我在台大經濟系畢業紀念冊上寫的畢業感言嗎?您說我的文采真好。怎麼想出「經世濟民,乃若其情」這八個字。我那時在您法學院研究室中傻傻地笑著說:「想著老師表面嚴肅,內心溫暖的臉龐,我就寫出來了。」然後我們一起大笑。

老師,要看到您的笑容真不容易啊。我一直珍藏著一些。這時黯淡的夜,校園鐘聲響起。必須停筆。催促著我去盡一個做為大學教授的責任。春風化雨。百年樹人。接續您的事業。 父親。作為您思想上的兒子,我會繼續您的事業與看顧師母。老師,明天去您家憑弔時,我會跟師母請一張您的照片。放在我的研究室案頭。安我腳步。慰我心傷。雖然我知道您在天國會一直看顧著我。老師。研究室外黯淡的夜有盞孤燈在那裡兀自明亮著。人影。想像中或者真的來臨。檀香裊裊。這時穿出了隔絕的玻璃。您和我。死與生。慢慢與那光線結合。我的明燈彼岸仍在。中間踏空與墜落的落葉,無聲無息。彷彿只是謠言與傳說。

(2008.11.05)